|

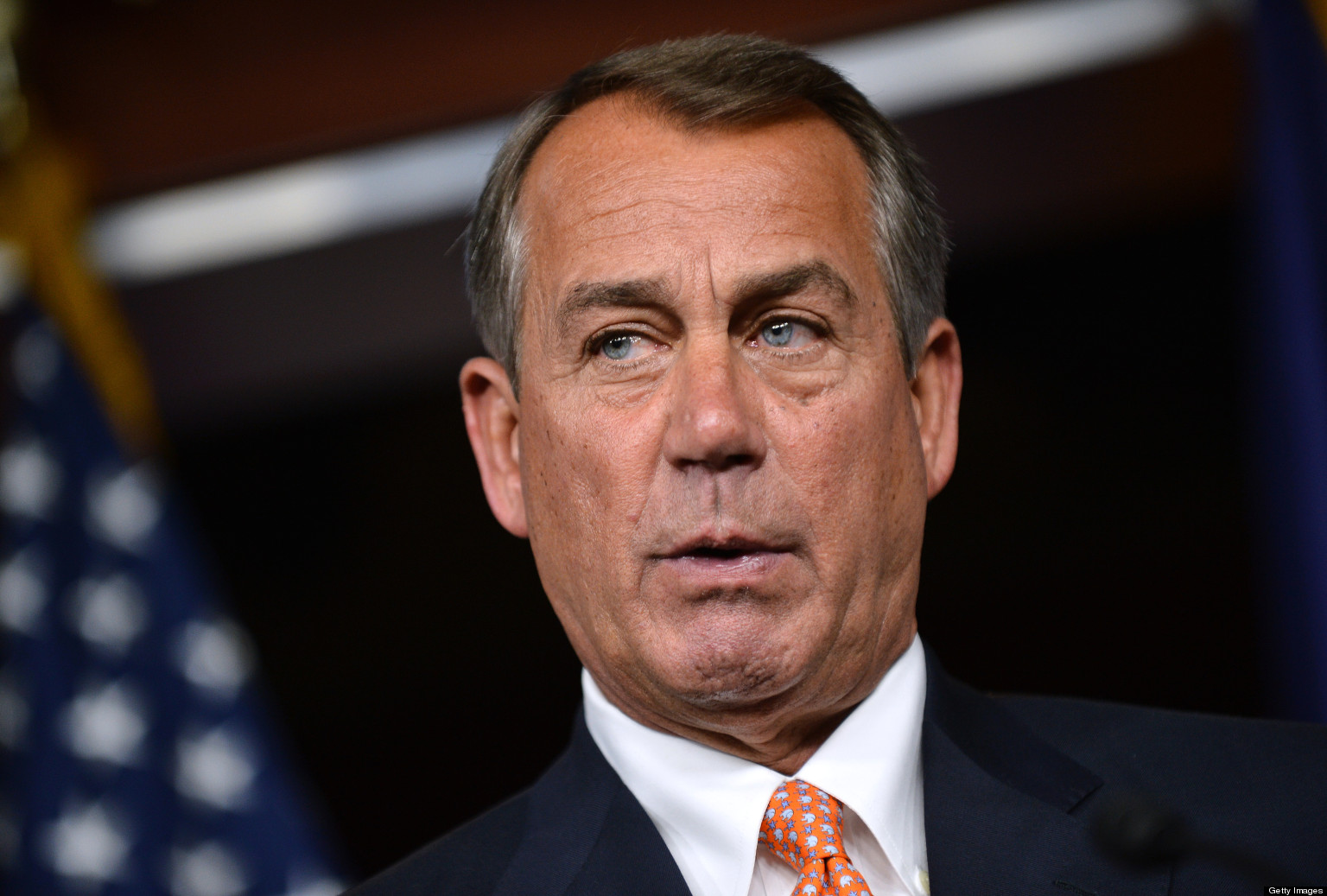

| Paul Krugman |

I've long admired Brad DeLong, economics professor at Cal Berkeley, for both his approach to his craft and his head-on, no-prisoners criticism of those with whom he disagrees, especially with the policy implications of such beliefs. In this he is very much like Paul Krugman. If I don't look to DeLong's blog often enough, I can rely on Krugman to give me a heads up, as he did today. DeLong offers

a draft of his ideas on the size of government and the proper level of public debt to support that government. Unsurprisingly, as the good liberal he is, he wants to grow the government in the 21st century and grow the public debt to sustainable levels in line with the size and role of government he envisions in the young century.

Here's

Krugman's analysis:

What Brad argues are two propositions that run very much counter to the

prevailing wisdom, especially among Very Serious People. First, he

argues that we should not only expect but want government to be

substantially bigger in the future than it was in the past. Second, he

suggests that public debt levels have historically been too low, not too

high...

So, how big should the

government be? The answer, broadly speaking, is surely that government

should do those things it does better than the private sector. But what

are these things?

The standard, textbook

answer is that we should look at public goods — goods that are non

rival and non excludable, so that the private sector won’t provide them.

National defense, weather satellites, disease control, etc.. And in the

19th century that was arguably what governments mainly did.

Nowadays, however,

governments are involved in a lot more — education, retirement, health

care. You can make the case that there are some aspects of education

that are a public good, but that’s not really why we rely on the

government to provide most education, and not at all why the government

is so involved in retirement and health. Instead, experience shows that

these are all areas where the government does a (much) better job than

the private sector. And Brad argues that the changing structure of the

economy will mean that we want more of these goods, hence bigger

government.

|

| Brad DeLong |

Right on point. during the last thirty-five years, since Ronald Reagan flagged the government as the problem rather than the solution, there's been -- except on defense -- a general movement on the right to degrade government until, as antitaxer Grover Norquist famously said, we could "drown it in the bathtub."

Of course, when there's a Katrina, that's different. When there's a 9/11, that's different, all of a sudden first responders become our heroes. Those, er, first responders are government workers. All of a sudden we like them, we

demand them.

But on so many fronts -- even first response -- government continues to degrade, and there's a cost to that. What government did well -- mandating retirement preparation, for example -- now the government is stymied by Very Serious People in the center, and low-tax denizens on the right, who argue that individuals sink or swim based on their own skills or dumb luck. But that's not enough by any measure. Left to themselves, people make a myriad of bad choices.

Now, the fact is that

people make decisions like [education, retirement planning, healthcare insurance, saving for the future] badly. Bad choices in education are the

norm where choice is free; voluntary, self-invested retirement savings

are a disaster. Human beings just don’t handle the very long run well —

call it hyperbolic discounting, call it bounded rationality, whatever,

our brains are designed to cope with the ancestral savannah and not

late-stage capitalist finance.

When you say things

like this, libertarians tend to retort that if people mess up on such

decisions, it’s their own fault. But the usual argument for free markets

is that they lead to good results — not that they would lead to good

results if people were more virtuous than they are, so we should rely on

them despite the bad results they yield in practice. And the truth is

that paternalism in these areas has led to pretty good results —

mandatory K-12 education, Social Security, and Medicare make our lives

more productive as well as more secure.

That's a major point and one that bears repeating: You can believe in free markets all you want, but if a market fails, like the 401(k) retirement system or the healthcare market in general, then we have to abandon that market. Healthcare isn't workable in a free marketplace. We don't "consume" healthcare in the sense that some of us drive Ford Focuses and some of us prefer BMWs. When you're sick, you want a Cadillac surgeon, not a ten-year old Vespa. No one says, "I want to live, but my choices to consume healthcare are limited, so, hell, it's my funeral!" Living or dying based on dumb luck or bad choices shouldn't be the default system in a society that can provide healthcare to all.

There is no successful market for that, and people have shown that free-to-make-all-your-decisions-individually-oh-well-I-screwed-up-ha-ha-c'est-la-vie doesn't have to be the way we roll when

government has a role in serving the public good so that such pitfalls are minimized. (And that's good for productivity and hence business!)

If business kills the pensions of yesteryear and the 401(k) fails to deliver -- and people are shown to vastly undersave for their retirements -- the cure is for government to step in and fix it, like expanding Social Security, not cutting it. That leads to more consumption and, yes, it's good for business!

Policies of the past thirty-five years -- not all administrations! -- haven't, on balance, done enough to prevent income inequality and bubble economics. In fact, major players like Larry Summers warn that we're in for

secular stagnation, a long, dark winter of economic doldrums. It might even be the default position moving forward. Demand-side growth can't happen if you suppress wages enough and undercut the "good" government spending, the good government roles. And the crazy thing is that we can afford to do more. Deficits are dropping and debt levels are, as well.

Conservative heads might explode at this, but there you are. And as I'm fond of saying, it's the family values, stupid. Undercut the least of us, and the best of us will fall eventually. Castles made of sand, anyone?

|

The Walmart way: People on food stamps served by workers on food

stamps, while six Walton heirs have a greater combined wealth than

that of 100,000,000 Americans. That's not sustainable, and it's not right. |